Investments not classified as either equity or fixed income are often called “alternative investments.” One that has gained a lot of attention recently is private equity. Investors are asking how private equity works and if this mysterious asset class is right for them. To answer these questions, let’s walk through a hypothetical example to better understand these investments and the key players involved.

Imagine five seasoned executives skilled at building manufacturing companies teaming up. Their goal is to seek out firms that exhibit potential but need help to grow. They form an investment fund to buy “private” companies, or those whose stock are not listed on a public stock exchange. These five executives are considered the “general partners,” or GPs for short, and they are responsible for managing the fund.

These executives have decades of experience and are confident they can help companies grow. They also know they must do more than tell existing management what needs to be done. Instead, they need control over the day-to-day activities such as operations, financials, personnel, etc.

Few companies will hand over the reins to outsiders, so the team must buy enough of each target company’s stock to gain control. These purchases can take hundreds of millions of dollars, so they raise money from two primary sources.

The first is from traditional bank loans, where the GPs borrow funds from multiple banks and pay interest on these loans over time. The second is from outside investors willing to share the risk for a piece of the return. They are called “limited partners,” or LPs for short because they have limited involvement in the fund.

The LPs rarely invest all of the committed capital upfront. Instead, the GPs will periodically do a “capital call” as they encounter investments. For example, if a pension fund committed $10 million to this private equity fund, it usually would not wire all the money to the fund on day one. If the GPs found a company to buy in Year 2 and “called” 20% of the capital from all the LPs to buy the target business, the pension fund would then send a check for $2 million ($10 million x 20% = $2 million) representing their share of the investment.

Once the GPs secure the capital, they need to hire personnel, rent office space, and do everything a company needs to do to stay in business. They charge the LPs a management fee to pay for it all and compensate the GPs for doing the heavy lifting. This fee ranges between 1% to 2% annually, so if the fund calls $50 million from LPs and charges a 2% management fee, then the GPs would use $1 million of the funds called ($50 million x 2% = $1 million) to pay its expenses in the first year.

The GPs do not work as hard as they do to earn a management fee. Instead, their goal is to profit from the sale of the fund’s investments. For example, suppose this fund invested $20 million of the capital raised into a small manufacturing company that was sold five years later for $200 million. In that case, both the GPs and LPs will realize a big return on their investment.

The profit split varies, but the industry average is 20% for the GPs and 80% for the LPs. The percentage GPs keep is called the “carried interest,” which can add up to huge amounts of money. For example, if the profits from the sale were $150 million after the debt was paid back, the GPs and LPs would keep the rest. The GPs take home $30 million ($150 million x 20% = $30 million), split amongst five people.

PUBLIC VS. PRIVATE

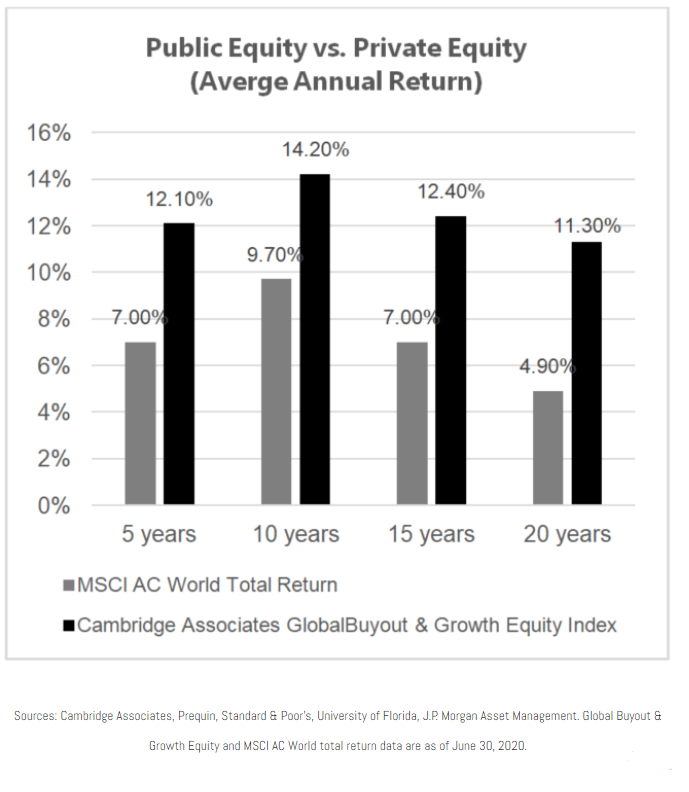

The chart below compares the average annual return of the Cambridge Associates Global Buyout & Growth Equity Index (private equity industry performance) to the MSCI World Total Return Index (global public equity market performance).

Based on these indices, private equity has more than doubled the return on public equity over the last 20 years. These impressive returns are due to several factors, but arguably the most important is control. The GPs can replace management, change a company’s strategic direction, sell off unprofitable business units, etc.

Furthermore, private equity can be incredibly sophisticated and often requires a team of seasoned executives who have spent years cutting their teeth in an industry. This creates high barriers to entry when compared to public equity markets.

However, this control comes at a price. When an investor buys a publicly traded stock, that transaction is conducted in seconds on a highly regulated exchange. Private equity deals take months, sometimes years, to complete. Both sides spend real money on lawyers and experts in everything from valuation and earnings quality to human resources (costs that are rarely recouped if a deal falls through).

Another challenge with private equity is the time horizon. Most investments require capital to be locked up for at least 5-7 years, and investors are often required to invest additional money along the way.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Direct investment into private equity funds had historically been restricted to institutions and ultra-high-net-worth investors for several reasons. First, investment minimums were often as high as $5-10 million per fund, so building a diversified allocation to private equity ran in the tens of millions.

Second, gaining access was not easy. Often, a prospective LP could only get in by knowing the right people or bringing more than just capital to the fund, such as specific expertise that the GPs could use. Lastly, conducting proper due diligence on private equity funds requires highly specialized expertise. Gaining access to these resources was just as hard as finding the funds themselves.

The good news is that many of these barriers have come down. Financial advisors with the acumen and access to private equity can now invest clients of all sizes into new fund structures that don’t require ongoing capital calls. Some even offer quarterly liquidity, so investors don’t have to lock up their money for years.

The bottom line is that the democratization of private equity and other alternative asset classes could become a major achievement in financial services over the next decade, but only if investors are willing to open their minds to trying something new. Just be sure to work with an advisor with proven experience because private equity carries unique risks that must be monitored and addressed from day one.

Sincerely,

Mike Sorrentino, CFA

Disclosures